The Lives of Individual African Americans in Massachusetts after the End of Slavery

~Samuel Stillman, 8 April 1784

Individuals who were formerly enslaved in Massachusetts continued to live in an inferior social position, legally free but with fewer civil rights than whites. They were treated equally by the legal system, but they could not serve on juries. They paid taxes, but could not vote, and, in most cases, their children did not attend public schools, prohibited at least by custom and tradition, if not by law. It was difficult to find work. Domestic service remained a viable employment, along with common labor and the professions associated with the sea. However, fear of kidnapping (and a forced return to enslavement elsewhere) was a bar to working on the waterfront or at sea. Indentured servitude also remained in force after the abolition of slavery, and African American children such as Dick Morey were commonly indentured out until they reached the age of 21. Free Black people in the north were continually organizing their communities in hopes of winning freedom for enslaved people elsewhere, and for bringing the benefits of full citizenship to all Black people. They built community associations that provided mutual support and a foundation for political action, such as the African Society in Boston, and the African Lodge of Masons.

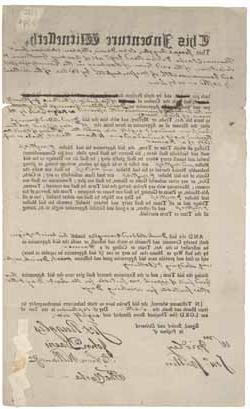

Indenture between David Stoddard Greenough and Dick Morey, witnessed by selectmen of Roxbury, 6 September 1786

Indenture between David Stoddard Greenough and Dick Morey, witnessed by selectmen of Roxbury, 6 September 1786

Bill of sale from John Mory to David Stoddard Greenough for Dick (an enslaved person), 30 July 1785

Bill of sale from John Mory to David Stoddard Greenough for Dick (an enslaved person), 30 July 1785

Prince Hall

Prince Hall was one of the most prominent free Black citizens of Boston during and after the Revolution. Born around 1735, of uncertain origins, he was enslaved by William Hall of Boston, who manumitted him in 1770 shortly after the Boston Massacre. Prince Hall worked as a leatherdresser and caterer, and was the Grand Master of the African Lodge in Boston. Another institution to promote social, political, and economic improvement for African Americans was the African Society formed in Boston in 1796. Although Prince Hall apparently was not a founding member of the African Society, the group did share a number of members with the African Lodge.

Prince Hall worked tirelessly for the abolition of slavery, for a legal end to the domestic sale of enslaved people in Massachusetts, and for free public education for the children of Black taxpayers in Boston. A group of Black Masons led by Prince Hall petitioned the General Court in February of 1788 to put an end to the sale and trade of enslaved people, a petition prompted by the abduction of three free Black men in Boston Harbor, who were lured aboard a vessel and subsequently taken to the West Indies to be enslaved. As a result of this petition, along with one put forth by the Quakers and one by the Boston clergy, the General Court passed an act on 26 March 1788 "to prevent the Slave Trade, and for granting Relief to the Families of such unhappy Persons as may be Kidnapped or decoyed away from this Commonwealth" (Kaplan p. 210). Prince Hall died in Boston in 1807.

Laws of the African Society, Instituted at Boston, Anno Domini 1796

Laws of the African Society, Instituted at Boston, Anno Domini 1796

Petition of Prince Hall to the Massachusetts General Court, 27 February 1788

Petition of Prince Hall to the Massachusetts General Court, 27 February 1788

Mary Hartford

The remarkable collection of the papers of the ancestors of Mary Hartford, a "colored woman who lived in the Belknap family from a child," documents the lives of free Black people after the Revolution. The manuscripts all relate in some way to ancestors of Mary Hartford, who may have been born in 1792, and died in 1872. Hartford, who saved the papers until her death, always maintained that they belonged to her father, whose christened name was Hartford, but whose surname may have changed frequently depending upon the name of his employer, as was common for African Americans, either enslaved or free. Thus, the frequency of the name Hartford: Hartford Turner, Hartford Robbins, Hartford Roberts, and Hartford Broom; and a woman named Dinah: Dinah Keeth, Dinah Hewes, Dinah Roberts, and Dinah Hartford. The collection highlights the difficulty of positively identifying individual members of early African American families, particularly due to the problem of names, and the paucity of surviving records.

Mary Hartford Papers

- Receipt from Katho Lame to Harford [Hartford] Broom, October 1783 - 24 May 1784

- Document by Samuel Stillman certifying that Hartford Turner and Dinah Ned were married by him, 8 April 1784

- Note from Edmund Ranger to Capt. Robins with instructions to let Mr. Hartford have wood, 15 March 1785

- Receipt from Cato Gray to Hartford Turner, 6 April 1785

- Receipt from France Swalus to Hartford Robberts, 29 April 1784 or 1785

- Receipt from Elizabeth Fennecy to Hartford Broom, 6 October 1785

- Note from Nathaniel Appleton to Judge Wendell, about Dinah, 28 February 1786

- Promissory note from Hartford Broom to Elizabeth Fennecy, 7 April 1786

- Tax certificate to Arford Broom [Hartford Broom], 22 August 1786

- Bill from Hartford Robbins to Mr. Calf, 21 August 1786

- Manuscript copy of the Lord's Prayer, circa 1785-1786

- Note from Dorothy Forbes to Charles Hayden, 30 June 1786

- Bill from Cato Hunt to Hartford Turner, 1787

- Letter from unidentified sender [possibly Dinah Roberts] to unidentified recipient, 11 August 1788

- Receipt from Charleston Soley to Hartford Roberts, 16 November 1787

- Receipt from Daniel Steward to Hartford Turner, 6 November 1788

- Receipt from William Turner, Jr. to Hartford Turner, 6 April 1789

- Receipt from Abraham Haskell to Hartford Turner, 12 August 1789

- Receipt from Venes Inchurs to Hartford Broom, 5 December 1789

- Receipt from Crumell Barns [Cromwell Barnes]to Hartford Roberts, 28 September 1791

- Receipt from Henry K. Stevenson to Dinah Roberts, 29 July 1806

- Bill from John G. Grossman to the estate of Dinah Hartford, signed by Sarah Belknap, 3 April 1813

- Bill from Parker Emerson to John Belknap, 29 April 1813

Next essay: St. George Tucker's Queries on Slavery in Massachusetts >